U.S. Dietary Guidelines 2025–2030 Explained: Why “Eat Real Food” Is the New Core Principle

On January 7, 2025, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Agriculture jointly released the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030. On the official U.S. government website, the guidelines are described as follows: “Under the bold leadership of President Trump, this edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans will reset federal nutrition policy, put our families and children first, and move toward a healthier nation.” Accompanying this is a very Trump-style slogan: “Make America Healthy Again.”

Why the need to be “healthy again”? Because the United States is facing a severe public health crisis: 50% of Americans have prediabetes or diabetes, 75% of adults have at least one chronic disease, and nearly 90% of healthcare spending goes toward treating chronic conditions. Most of these diseases are closely linked to diet and lifestyle.

In response, the new guidelines position themselves as a “reset of nutrition policy”—a phrase that is itself quite thought-provoking. Is the U.S. government openly “slapping itself in the face” over decades of past dietary advice? In theory, as a global leader in nutrition research, such a major policy shift should carry considerable guiding significance. Yet the heavy Trump imprint on the document also makes it feel somewhat less reliable.

So what does this set of guidelines actually say? What does it emphasize? And how much reference value does it really have? Setting other factors aside, let’s focus on the substance and talk about this latest edition of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines.

Author’s note: The following content is my own reorganization and summary based on reading the guidelines and consulting additional sources. It does not fully follow the original structure or wording of the official document and represents only my personal views. Readers who are interested can consult the original guidelines via the link at the beginning; it is only about 10 pages long and easy to read.

One Core Principle: Eat Real Food

On the very first page of the guidelines, a simple and direct core principle is stated upfront: “Eat Real Food.”

At this point, some readers might ask: real food? So what have I been eating before—fake food?

So what exactly counts as “real food”? On the official website, I found a clear definition:

Foods that are whole or minimally processed and still recognizable as food. Prepared with very few ingredients, and without added sugars, industrial oils, artificial flavors, or preservatives.

This definition highlights two key characteristics. The first is the integrity and original form of the food—for example, whole fruits and vegetables are preferred over juices or extracts. The second is the purity of the ingredients. A popular way to put it is: if your grandmother can’t understand the ingredient list, then it probably isn’t “real food.”

Why emphasize this? Because real food is a “whole system,” not just a simple stack of nutrients. Take an orange and a glass of orange juice as an example. On a nutrition label, the vitamin C content of the two might look similar. But a whole orange contains intact dietary fiber, which slows digestion, leads to a steadier blood sugar response, and provides greater satiety. Once it’s juiced, the fiber is gone and the sugars are concentrated—drink a glass and your blood sugar spikes, and you’re hungry again soon after. The source is the same, but the effects on the body are completely different, and this difference is something nutrition labels cannot capture.

The guidelines also use the term “nutrient-dense”: real food provides more nutrition with fewer calories. Ultra-processed foods are the opposite. To extend shelf life, improve taste, and reduce costs, they often remove some natural components and add sugar, salt, fats, and various additives, delivering what is essentially “empty calories.” In a previous randomized controlled trial, researchers found that even when the nutrient composition was matched as closely as possible, participants ate more and gained weight more easily during the ultra-processed food phase than during the unprocessed or minimally processed diet phase.1

This also helps explain why the previous line of thinking had its limitations. Over the past few decades, mainstream discourse has leaned heavily toward a nutrient-centered framework (such as low fat, low calories), which has produced side effects in the context of the modern food industry. For example, how many grams of protein we should consume per day, how many grams of carbohydrates, how strictly we should control calories and fat—as if healthy eating were a precise math problem. When experts tell you that “fat is the enemy and must be controlled,” food manufacturers respond by rolling out all kinds of “low-fat” products. These products do contain less fat, but to make up for the loss in taste, they often add more additives. Under the old framework, such foods were considered perfectly “compliant,” yet they are in fact典型 examples of ultra-processed foods.

Once you understand this, the logic behind the current shift becomes much easier to grasp.

And this shift is not a spur-of-the-moment decision. A large umbrella review published in The BMJ in 2024 (an umbrella review further analyzes the results of multiple meta-analyses and therefore carries a higher level of evidence) compiled data from nearly ten million people. The results showed that ultra-processed foods are significantly associated with multiple health risks: a 21% increase in all-cause mortality, a 66% increase in death from heart disease, and a 40% increase in the risk of type 2 diabetes. What is even more telling is that not a single study found any health benefit from ultra-processed foods.2

It is clear that this viewpoint is actually in line with the mainstream direction of research in recent years and is by no means some “earth-shattering” new discovery. Personally, I even find the term “reset” a bit overstated, carrying a hint of political messaging. But setting the wording aside, it does represent a shift in official thinking. Academia has been moving in this direction for quite some time; this is simply the moment when the authorities formally acknowledged and summarized that shift.

In any case, at least with regard to this core principle, it is backed by solid research and evidence.

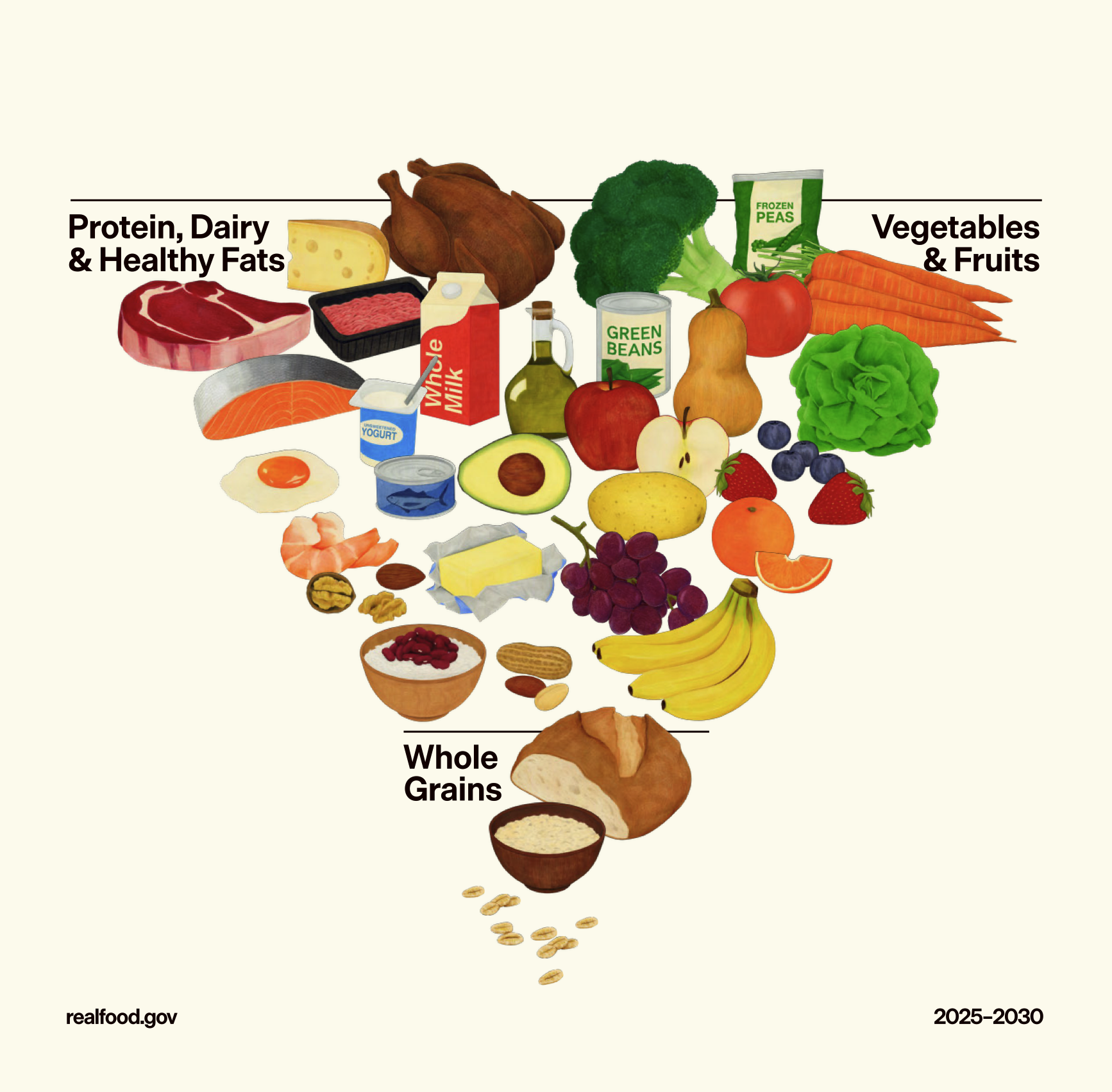

Three Priority Shifts: The Inverted Food Pyramid

Beyond the change in core philosophy, the most striking update in the new guidelines is the inversion of the food pyramid. This visual shift is not merely a design refresh, but a reordering of priorities in the overall nutritional structure.

Back in 1992, the United States introduced a very classic food pyramid model: bread, rice, noodles, and other grains sat firmly at the base, recommended for the highest intake; above them were fruits and vegetables; higher still were dairy and meat; and fats and sugars were squeezed into a tiny triangle at the very top. This image shaped an entire generation’s understanding of what “healthy eating” looks like.

In the new pyramid, the top section—the part that should be prioritized the most—is divided into two sides: on the left are protein, dairy, and healthy fats; on the right are fruits and vegetables. Grains, once considered the “foundation” of the diet, have now been compressed into the narrowest section at the bottom, with a special emphasis on “whole grains.”

This change directly reflects a restructuring and reprioritization of the three major macronutrients—protein, fat, and carbohydrates.

Left: the classic 1992 food pyramid; right: the new inverted food pyramid

Change One: Protein First — Make Sure You Get Enough Protein at Every Meal

The most eye-catching shift in the new food pyramid is that protein has jumped from a middle position—where it was something to be limited—to the very top as the highest priority. The wording in the guidelines is quite direct: “Prioritize high-quality protein at every meal.” In other words, if conditions allow, you should aim to meet your protein needs first, and then consider pairing it with other foods.

The specific target is 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day, almost double the previous recommendation of 0.8 g/kg. For a 70-kg adult, this means about 84–112 grams of protein per day instead of the old 56 grams. That number may sound abstract, so translated into food it looks roughly like this: 100 grams of protein is about 500 grams of lean meat (two large chicken breasts or two large steaks), or about 1 kilogram of tofu, or around 15 eggs. Of course, no one eats just one food source; in practice, it’s better to mix high-quality animal and plant sources such as eggs, poultry, seafood, red meat, legumes, and nuts.

At its core, this change is a correction—from “preventing deficiency” to “promoting optimal health.”

Starting in the 1950s, “saturated fat causes heart disease” gradually became the mainstream consensus in nutrition science. Meat, eggs, and dairy—major sources of high-quality protein—also contain fat, so they were lumped together and labeled as foods to be restricted. Once protein and fat intake were limited, the remaining calorie gap naturally had to be filled by carbohydrates. Because carbs are very low in fat, they were seen as a “safe” energy source and took center stage.

There were also some less-than-glorious forces at work in this process. In the 1970s, the U.S. had a grain surplus, and dietary guidelines became, to some extent, a policy tool to clear inventory. Research funded by the sugar industry deliberately downplayed the harms of sugar and shifted the blame onto fat. Lobbying from the meat and dairy industries even delayed the release of the original 1991 pyramid by a year, and in the final version the recommended grain intake was higher than what nutrition scientists had initially proposed. Science, politics, and business were all stirred together in the same bowl, and the “authoritative advice” eventually served up was no longer a purely scientific conclusion.

In recent years, however, research has begun to shake the assumption that “fat is harmful” (more on this below). Naturally, protein-rich foods that were restricted simply because they contained fat deserve to be re-evaluated. Scientists have also realized that the old recommendation of 0.8 g/kg was set as a minimum to “prevent deficiency.” It’s like a passing score of 60—no one would argue that scoring 60 is the optimal state.

On one hand, evidence supporting higher intake has been accumulating. Multiple large studies in recent years show that higher protein intake is closely associated with better blood-glucose control, stronger satiety, and healthier muscles and bones. For middle-aged and older adults in particular, adequate protein is key to preventing muscle loss.

On the other hand, there is currently no solid evidence that high-protein diets are harmful. A 2018 meta-analysis found no adverse effects of high protein intake on kidney function in healthy adults, and similarly found no evidence of harm to liver function.3

But “no problems found” is not the same as “proven to be completely safe.”4

First, most existing studies last no more than six months, so long-term effects remain uncertain.

Second, the source of protein matters. A study involving nearly 12,000 people found that higher intake of red and processed meat significantly increased the risk of chronic kidney disease, while replacing red meat with plant protein was associated with lower risk. In other words, even at the same “high-protein” level, fish, poultry, eggs, and legumes may have very different effects on the body compared with bacon, sausages, and deli meats.5

In addition, it’s worth being alert to the potential digestive burden of high protein intake, the risk of acid–base imbalance, and possible immune or inflammatory responses. If you usually consume little protein or have a sensitive digestive system, you should increase your intake gradually. If you already have kidney disease, liver disease, gout, or other immune or metabolic conditions, raising protein intake rashly may carry risks, and it’s best to consult a doctor before adjusting your diet.

Moreover, in research terms, a diet is generally considered “high protein” only when daily intake exceeds about 1.5–2.0 g per kilogram of body weight. The guideline’s recommendation merely sits around this threshold; it is not blindly promoting “high-protein diets.”

In short, elevating the “priority” of protein is a good choice for most healthy people, but it does not mean unlimited consumption. A more sensible approach is to prioritize high-quality protein sources, moderately increase the proportion, and stay cautious about processed meats.

Change Two: Clearing Fat’s Name — Moderate Intake of Healthy Fats

If protein is an “upgrade,” then fat is more like a “rehabilitation.”

The fear of fat in the past stemmed from the hypothesis that “saturated fat causes heart disease.” In recent years, however, this hypothesis has been increasingly questioned, and the evidence now calls for a more nuanced view. A meta-analysis published in The BMJ in 2015, combining data from hundreds of thousands of people, found no significant association between saturated fat and either cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality. 6In 2020, the Cochrane Database—widely regarded as one of the highest standards of evidence-based medicine—published a systematic review with a more complex conclusion: reducing saturated fat intake does lower the risk of cardiovascular events by 17%, but it has no significant effect on all-cause mortality or cardiovascular mortality.7

Saturated fat may not be the “final boss” we once thought it was, but it is not completely harmless either. It may not be a health food, but it is far from so evil that it must be eradicated at all costs. Moreover, fat itself is an essential nutrient and plays multiple roles in the human body. A lack of fat can impair the absorption of vitamins A, D, E, and K; affect the synthesis of steroid hormones, including estrogen and testosterone; and disrupt energy metabolism and blood sugar stability.

What truly deserves vigilance is trans fat. Studies show that trans fat is significantly associated with a 34% increase in all-cause mortality and a 28% increase in deaths from coronary heart disease.8The key difference lies in their sources: saturated fat mainly comes from natural animal fats and some plant oils, whereas trans fat is primarily a product of industrial processing, commonly found in hydrogenated vegetable oils, margarine, puff pastries, and fried foods. In the past, we lumped “natural fats” and “artificial fats” together. While this did not spare the latter, it likely led us to over-demonize the former.

The guidelines also clearly list sources of healthy fats: meat, eggs, seafood rich in omega-3 fatty acids, nuts, seeds, full-fat dairy products, olives, and avocados. For cooking oils, olive oil—rich in essential fatty acids—is recommended as a priority, while butter or beef tallow can also be considered as options.

That said, “clearing fat’s name” does not mean “eat as much as you want.” It must be emphasized that the studies above only indicate that saturated fat is not significantly associated with those very severe health risks; they do not suggest that eating more saturated fat brings extra health benefits. This point remains debated in academia, and the guidelines do not give a definitive answer, instead recommending that saturated fat generally account for no more than 10% of total daily calories.

What does this 10% mean in practice? For an adult consuming 2,000 calories per day, the upper limit for saturated fat is about 22 grams—roughly the amount found in 100 grams of pork belly, or three cups of whole milk, or one steak. So you still cannot indulge in braised pork or chug whole milk without restraint.

The core message of the new guidelines is: there is no need to be overly afraid of natural fats, but moderation and balance remain the unchanging principles.

Change Three: Carbohydrates Demoted — From Foundation to Supporting Role

If protein is an “upgrade” and fat a “rehabilitation,” then carbohydrates are a “demotion.”

The 1992 food pyramid recommended 6–11 servings of carbohydrates per day, the highest among all food groups. The new guidelines compress the recommended intake of whole grains to 2–4 servings per day and describe refined carbohydrates as something to be “significantly reduced.” White bread, instant breakfast cereals, and cookies are explicitly called out, while whole grains—such as oats, brown rice, quinoa, and true whole-wheat bread—are clearly favored.

This “demotion” has a theoretical basis. From a physiological perspective, there are “essential amino acids” and “essential fatty acids”—substances the human body cannot synthesize and must obtain from food. But there is no such thing as “essential carbohydrates.” The body can produce glucose on its own through gluconeogenesis, using protein and fat. This means that in terms of calorie allocation, carbohydrates are the most “replaceable.” When we raise the priority of protein and healthy fats, the proportion of carbohydrates naturally needs to be reduced.

Reducing refined carbs and increasing whole grains is also strongly supported by evidence. A systematic review in The Lancet analyzing hundreds of prospective studies found that people with the highest fiber intake had 15–30% lower risks of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and colorectal cancer compared with those with the lowest intake.9 A meta-analysis in The BMJ found that increasing whole-grain intake by three servings per day reduced the risk of coronary heart disease by 19% and all-cause mortality by 17%. Refined grains and white rice, by contrast, showed almost no similar protective effect.10

That said, this does not mean carbohydrates should be pushed extremely low. Another large study published in a Lancet sub-journal revealed a U-shaped curve: when carbohydrates provide less than 40% or more than 70% of total energy, mortality increases; the optimal range is around 50–55%.11 The new pyramid may look radical at first glance, with grains squeezed into a small corner at the bottom. But if you do the math, 2–4 servings of whole grains per day amount to roughly 150–200 grams of cooked staple foods. Add in the refined carbs that are hard to avoid completely, plus the natural carbohydrates in vegetables, fruits, and dairy, and the total is not extreme at all. This is not telling you to “eat meat as your staple,” but rather to adjust the priorities among different food groups.

As for replacing all white rice and white flour with whole grains, there is no need to go to extremes either. Whole grains are high in fiber, and a sudden large increase can cause bloating and digestive discomfort—especially for older adults and those with sensitive digestive systems. A more practical approach is to raise the proportion gradually: mix some brown rice or quinoa into white rice, choose whole-wheat bread, try oatmeal for breakfast—step by step rather than all at once.

It is also important to be wary of taking these guidelines out of context to promote extremely low-carb or ketogenic diets. The guidelines do note that “some people with chronic conditions may see improvements in health when following a low-carbohydrate eating pattern,” but immediately add that this should be done “in partnership with your healthcare professional to determine and adopt an eating plan that is appropriate for you and your health status.” The same applies to ketogenic diets: they are essentially therapeutic diets, not lifestyle trends that the general public should follow casually.

So the core message behind the “demotion” of carbohydrates is not that “carbs are the enemy,” but rather: eat less refined carbohydrates, eat whole grains in moderation, and adjust the exact proportion according to individual needs.

Six Dietary Health Recommendations

Beyond the reprioritization of the three macronutrients, I’ve also summarized six particularly important dietary health recommendations. These are more practical in nature: some are familiar old advice, while others are framed in newer ways.

1. Zero tolerance for added sugar

The guidelines state it very clearly: “No added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners are recommended or considered part of a healthy diet.”

The harms of added sugar have long been common knowledge—there’s probably no one who still doesn’t know this. But this may be the toughest stance an official institution has taken on sugar so far. The specific recommendation is to limit added sugar to no more than 10 grams per meal, and for children to avoid it entirely.

It’s important to clarify that this refers to “added sugar,” not sugars that occur naturally in foods. The sugar in whole fruits coexists with fiber, vitamins, and minerals, is digested and absorbed more slowly, and has a smaller impact on blood sugar, so it is not subject to these limits. However, sweeteners that sound “natural,” such as honey and maple syrup, are essentially no different from white sugar and are also classified as added sugars.

In addition, replacing real sugar with artificial sweeteners is not viewed favorably either. This position aligns with the World Health Organization’s 2022 review: after systematically examining a large body of evidence, the WHO explicitly recommended against using non-sugar sweeteners to control body weight or prevent chronic diseases. The reasoning is that while sweeteners may help reduce calorie intake in the short term, there is no clear evidence that they are beneficial for long-term weight control or health, and they may even carry potential risks.

Rather than obsessing over which sugar or sweetener to use, it’s better to reduce our dependence on sweetness altogether. Sugar-free cola is not a healthy drink—it is simply “less unhealthy.”

2. The Return of Full-Fat Dairy

This one is easy to understand: now that fat has been “cleared of its name,” the comeback of full-fat dairy is only natural.

As mentioned earlier, many low-fat products add sugar to make up for the loss of flavor. In addition, the fat-soluble vitamins in dairy products (A, D, E, and K) require fat for proper absorption—removing the fat means their nutritional value is effectively discounted. Some studies also show that full-fat dairy is more satiating and may help reduce overall calorie intake. Others have found no significant association between full-fat dairy and cardiovascular risk, and even links to lower risks of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

What’s more, the core value of the guidelines is to eat real food, and full-fat dairy is clearly more “real” than its skimmed counterparts. Of course, this doesn’t mean chugging whole milk by the liter. Rather, it means that when choosing dairy products, there’s no need to deliberately go for low-fat options—unsweetened is a higher priority than low-fat. At the same time, if you’re getting more fat from dairy, you should correspondingly reduce fat from other sources.

3. Pay Attention to Gut Health and Consume Fermented Foods in Moderation

In recent years, the gut microbiome has become a hot topic, with a surge of related research and a growing body of new evidence.

The guidelines state: your gut contains trillions of bacteria and other microorganisms, collectively known as the microbiome. A healthy diet supports a balanced microbiome and healthy digestion. Highly processed foods disrupt this balance, while vegetables, fruits, fermented foods, and high-fiber foods support a diverse microbiome. Fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, and miso are explicitly listed as recommended.

When it comes to fermented foods, Chinese people certainly have a lot to say: the pickled vegetables, fermented bean curd, pickled mustard greens, soy sauce, fermented black beans, and yogurt we commonly eat all fall into this category.

But here’s a splash of cold water. The health benefits of fermented foods mainly come from their probiotics and metabolic byproducts, which do help gut health. The problem is that traditional fermented foods are often accompanied by high levels of salt and sugar, and some may even pose a risk of nitrites. A small dish of pickled mustard greens can contain more than half of the recommended daily sodium intake. Compared with these issues, the benefits brought by probiotics may not be worth much.

If your goal is truly to promote gut health, you should choose low-sodium, low-sugar, or even sugar-free options, such as unsweetened yogurt or genuinely low-sodium fermented products. But to be honest, many products marketed as “low sodium” are only relatively lower—if you look closely at the nutrition label, the sodium content is still quite high. Truly low-sodium fermented foods are unlikely to taste very good.

4. Eat More Whole Fruits and Vegetables

The reasoning here has already been covered in the core principle section: whole foods are better than processed or extracted forms. Fruits and vegetables are best eaten whole, rather than juiced.

The guidelines recommend three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruit per day, and emphasize eating “a wide variety of colorful, nutrient-dense vegetables and fruits.” Different colors contain different phytochemicals, and a diverse intake is more beneficial than relying on a single type.

If fresh produce is not easily available, the guidelines also provide a hierarchy of alternatives:

- Best choice: fresh, whole fruits and vegetables

- Second best: frozen, dried, or canned fruits and vegetables with no added sugar

- Limited choice: 100% fruit or vegetable juice, diluted with water and consumed in small amounts

- Try to avoid: fruit and vegetable products with added sugar and various additives

5. Choose Healthier Cooking Methods

The guidelines recommend baking, roasting, stewing, stir-frying, or grilling instead of deep-frying.

It’s worth noting that “grilling” here most likely refers to the American cooking context: food cooked in an oven at around 180–220°C, often wrapped in foil, without open flames or heavy smoke, and not heavily charred. This is very different from the charcoal grilling we commonly see on the street, with open flames, thick smoke, and strong “smoky flavor.”

When meat is grilled over high heat and open flames, heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons can form—substances associated with increased cancer risk. Eating this occasionally is fine, but it is not recommended as a primary daily cooking method.

Another point to pay special attention to is avoiding repeated high-temperature deep-frying. The oil used in restaurants and fast-food outlets is often reused many times, leading to oxidation and the formation of harmful compounds. In home cooking, occasional deep-frying with fresh oil that is discarded afterward is not a major problem, but it can hardly be called healthy either. From this perspective, air fryers are a fairly good alternative.

6. Limit All Alcoholic Beverages

The guidelines state: “For better overall health, reduce alcohol intake.” People who should avoid alcohol completely include pregnant women, those recovering from alcohol use disorder, people taking certain medications, and those with a family history of alcoholism.

Notably, the new guidelines do not provide a specific number for “moderate drinking.” In earlier years, there were claims that moderate alcohol consumption—especially wine—benefited cardiovascular health. However, studies supporting this view were later found to have methodological problems, and in 2022 the World Heart Federation stated plainly: “There is no safe level of alcohol consumption that is beneficial for cardiovascular health.”12

At the end of the day, alcohol is a confirmed Group 1 carcinogen. It does harm and offers no health benefits—there is no such thing as “safe in moderation.” The new guidelines’ stance is simple: drink less if you can, and ideally not at all.

Summary

Overall, in my view, this set of guidelines represents an official summary and endorsement of the mainstream direction of research in recent years. It contradicts some points in earlier guidelines, but it is not a shocking revolution either. The inverted pyramid is a visual symbol of changing priorities, not a literal representation of how much to eat. When translated into actual grams and servings, the recommendations still fall within reasonable ranges. They are worth referencing, but it’s important to be wary of cherry-picked interpretations online.

Recommendations such as prioritizing protein and consuming moderate amounts of fat and carbohydrates all rest on one key premise: eating amounts that are appropriate for you. Calorie needs depend on age, sex, height, weight, and activity level—everyone is different. Moderation is the true foundation; talking about health without considering quantity, whether for protein, fat, or carbohydrates, is meaningless. And there is one more basic thing: drink water. Drink more water—plain water or sparkling water is the most cost-effective health investment you can make.

Final Notes

The guidelines also devote a substantial section to dietary recommendations for different population groups: infant and young child feeding (breastfeeding, vitamin D, the introduction of complementary foods, allergens, etc.), adolescent nutrition (calcium, iron, vitamin D, and avoiding energy drinks), priority nutrients for pregnant and breastfeeding women and for older adults, as well as considerations for vegetarian and vegan diets (such as limiting highly processed substitutes and monitoring key nutrients with appropriate supplementation strategies). Due to space constraints, I won’t go into detail here. Interested readers can consult the original document themselves—nowadays, with AI assistance, reading English materials is quite convenient.

Just like the 1992 guidelines, the new version inevitably carries the imprint of business interests, politics, and other factors; it can never be completely pure. Endorsement by the U.S. government does give it some guiding significance, but its real-world impact will still need time to be tested. In China, the current standard in use is the 2022 edition of the Chinese Dietary Pagoda, which shares some common ground with these guidelines but also differs in certain aspects.

Health is the result of many factors in balance, not something to be swayed by every new trend. If you follow whatever is praised today, then switch directions tomorrow when something else becomes fashionable, you may end up sticking with nothing at all. Take what is good, discard what is flawed, don’t follow blindly, and leave the rest to time.

In the end, eating healthily has never been easy. It takes time, energy, and money—and sometimes it means going against your own instincts. When you truly try to put it into practice, you realize that people with time may not have the means to buy a wide variety of ingredients, while those with the budget are often trapped in cycles of overtime work and takeout food. In a sense, “eating properly” can even be a bit of a luxury.

What’s harder still is that even if time and money are no longer problems, healthy eating also means saying goodbye to those cheap, easy pleasures. Sugar, oil, salt, refined carbs—the combinations that flood the brain with dopamine—are precisely the things the guidelines like the least.

By the time I got here, I started to feel a little hungry.

I looked at my desk: on one side was lactose-free, full-fat, additive-free fresh milk that perfectly fits the guidelines’ aesthetic; on the other was a deeply processed, ultimate sugar-and-fat combo that the guidelines would probably frown upon—a sugar-fried pastry. I’ll take both. Not exactly healthy, but perhaps the occasional bit of happiness is part of being healthy too.

Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):67-77.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

↩︎

Lane M M, Gamage E, Du S, Ashtree D N, McGuinness A J, Gauci S et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses BMJ 2024; 384 :e077310 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

↩︎

Devries MC, Sithamparapillai A, Brimble KS, Banfield L, Morton RW, Phillips SM. Changes in Kidney Function Do Not Differ between Healthy Adults Consuming Higher- Compared with Lower- or Normal-Protein Diets: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nutr. 2018;148(11):1760-1775. doi:10.1093/jn/nxy197

↩︎

French SJ, Kanter M, Maki KC, Rust BM, Allison DB. The harms of high protein intake: conjectured, postulated, claimed, and presumed, but shown?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2025;122(1):9-16. doi:10.1016/j.ajcnut.2025.05.002

↩︎

Mirmiran P, Yuzbashian E, Aghayan M, Mahdavi M, Asghari G, Azizi F. A Prospective Study of Dietary Meat Intake and Risk of Incident Chronic Kidney Disease. J Ren Nutr. 2020;30(2):111-118. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2019.06.008

↩︎- de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h3978. Published 2015 Aug 11. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3978 ↩︎

Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD011737. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. Accessed 12 January 2026.

↩︎- de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h3978. Published 2015 Aug 11. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3978 ↩︎

- Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):434-445. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9 ↩︎

Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, Fadnes L T, Boffetta P, Greenwood D C et al. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies BMJ 2016; 353 :i2716 doi:10.1136/bmj.i2716

↩︎- Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, Cheng S, et al. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(9):e419-e428. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30135-X ↩︎

Arora M, ElSayed A, Beger B, et al. The Impact of Alcohol Consumption on Cardiovascular Health: Myths and Measures. Glob Heart. 2022;17(1):45. Published 2022 Jul 22. doi:10.5334/gh.1132

↩︎

Leave a Reply